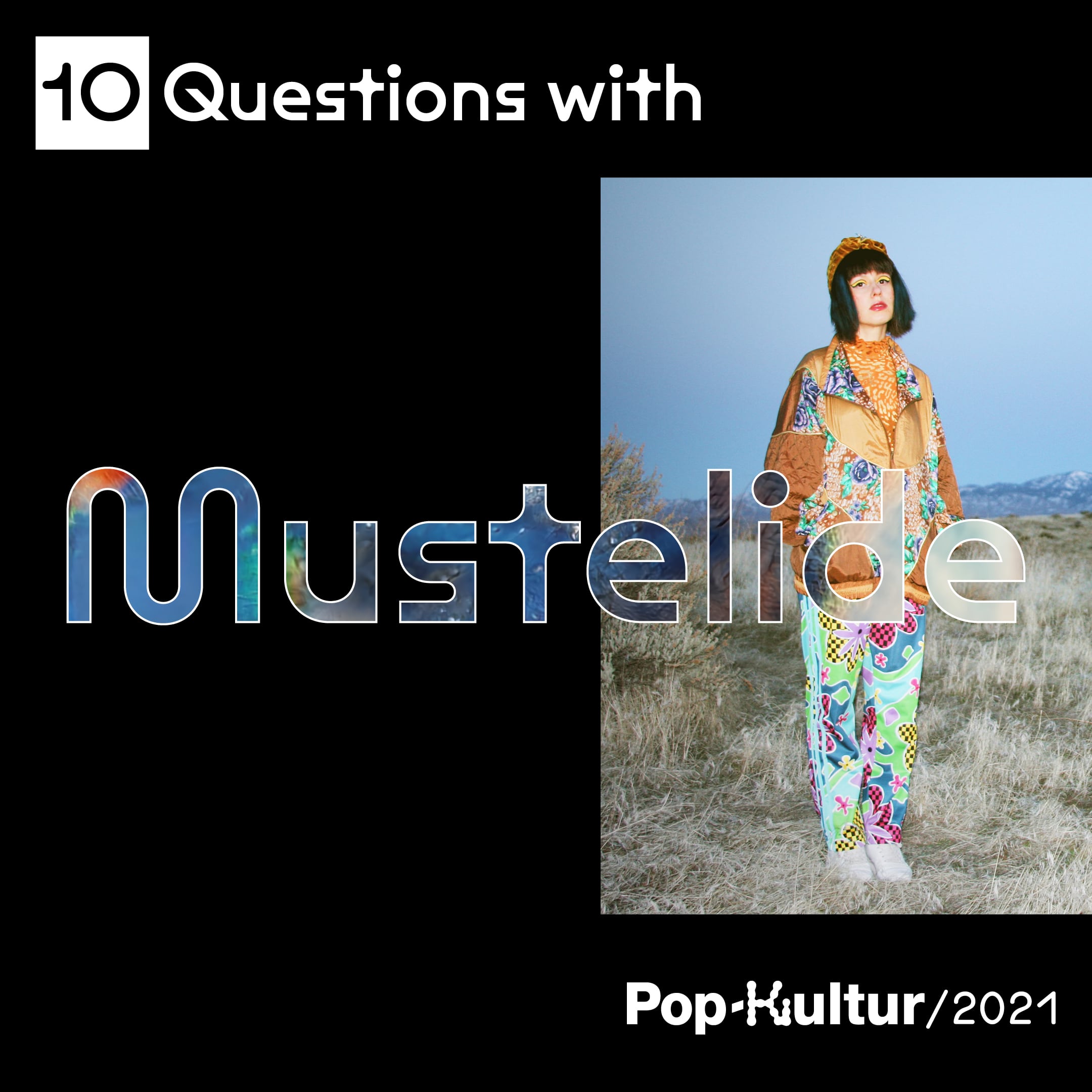

Our interview series »10 Questions with…« will introduce several of the acts from the lineup of this year’s Pop-Kultur festival that have earned a place in your playlists and hearts. Natallia Kunitskaya, who under the name of Mustelide weaves samples and synthesisers into danceable avant-pop, tells us about her path as a musician, which led from Belarus to Berlin. Today, she says, she’d live in Berlinsk. Natallia also talks about what you can do with broken instruments and about the political crisis in Belarus.

Hi Natallia, can you please explain, what is Berlinsk?

Berlinsk is a multidimensional place combining the two cities of Berlin and Minsk, as if they could be one. And it’s somewhere right in the middle of East and West. Berlinsk is where my heart is, ’cause I really love both the city where I’ve been born and the one where I’m living now.

Even when you were still living in Minsk, you were involved in various bands and projects. Can you tell us about that?

Good rock ‘n’ roll times! I’ve been playing in bands since I was 15, they were all kinds of music from the independent scene in Belarus: metal, rock, indie, prog-rock, cabaret. For example ULIS, one of the oldest Belarusian rock bands with lyrics in Belarusian, considered legendary. I was recruited to play synths with them when I was 17. With my first tours and big festivals, we were never playing in our homeland, because the band was forbidden there. And then Silver Wedding is a huge band consisting of some real characters and weirdos, with one of the most talented poets and artists from Belarus as the front woman, Svetlana Ben. We played self-made instruments and songs for children, and we also performed a cabaret programme based on texts by Bertolt Brecht. But I was secretly a fan of pop music all the way, a secret even to myself. Only now I understand how much the pop hits of the eighties and nineties affected me.

How did you come to realise that you prefer working on your own?

I think I’ve always been more on the composing and production side than into just playing instruments or singing. I’ve been very fascinated about writing songs since I was a child, but I was too shy to take on this challenge and the role of a producer. There were some scenarios in my head in which I saw myself only creating music as a part of a band, and where producers are authoritative guys sitting in their expensive studios. But as the time of DIY producers came and I got access to all production tools, like machines replacing musicians and Ableton replacing professional studios, it finally felt right for me to dive deep into the magical world of production and sound design.

For your last EP »Ginseng Woman,« you used samples of broken orchestral instruments. That sounds quite conceptual, but the result remains very musical. In a song like »Zver,« these instruments sometimes take over parts of a bass line, sometimes you use them like guitars, or they might drone a bit like foreign bodies in an otherwise very poppy song. How did this come about? What was the idea?

I always had been super passionate about analogue synthesisers and creating every sound from scratch. It was pretty hard to get them in Belarus, so every machine was a real treasure. My main goal was to create something unique but striking, like all this pop music I was in love with. But then I became thrilled about collecting samples and using them as a sound base. I realised how multifaceted and exclusive samples can be, because they capture a singular moment and its energy. So I started adding self-made environmental recordings cut into samples to my tracks. For example, I used the sound of an owl cry to make a drum part in my song »Opushka« and recorded the ambience at a flamenco dance event in Sevilla for »Nanoantenna.« Very intense.

And then guitars were smashed?

Nope. It was later that I heard about a project by Found Sound Nation, a non-profit organisation running an art residency. The project was about giving a new life to broken orchestral instruments from art schools in Florida. They collected about 800 of them, and then they had professional musicians recording with them in a studio. These recordings were then given to artists from all over the world to use in songs. The condition was that no other sounds were allowed to be used except the human voice. The challenge thrilled me so much that I couldn’t stop just with only one track. I made an entire album. I basically created my own synthesisers and drum machines with such a unique sound full of pain and hope, wisdom and wildness, because it seemed the soul of these broken instruments were preserved in the new sounds.

Apart from sampling, are there acts or (pop) cultural phenomena that you are particularly interested in at the moment?

Some of the pop artists who have hit me recently are, for example, Sega Bodega, Christine and the Queens, and Karma She. I absolutely loved the Appleville online festival by PC Music. I really enjoy the bits of chaos happening in pop music nowadays. It feels like pop culture was a lot about rules, and now there are no rules anymore, no definitions of what pop is. It’s now about catching people’s souls and making them fall in love for a moment. And the means of achieving that are so aplenty nowadays that pop is finally associated more with freedom. Pop can be popular for 100 people or a million. It’s not about the amount any more, it’s about how strong it hits. And the times when you could be ashamed for being a fan of pop music are gone. It’s all pop now, pretty much. Huge celebrities can do something completely weird and avant-garde, collaborate with independent artists and at the same time absolutely underground artists can play the pop-music game, becoming Britney in their bedroom. And that’s what I really love, it’s like a Alice In Wonderland scenario.

How would you characterise the pop scene(s) in Minsk? What are the major trends there, and how do they differ from, for example, your new environment in Berlin?

If we’re talking about artists in the independent pop scene, they create intuitively by feeling. There are no institutions, communities or even big clubs developing pop musicians. So the results can be really interesting and honest. Especially if artists stay true to themselves, not doing bad imitations of the West, which happens a lot as well. The Belarusian independent pop scene has a bit of a shy and traumatised character, depressed and dreamy, trying to escape into a self-made reality. That sounds a bit tragic, but it’s also charming. Pop in Berlin seems to be more liberated and sassy but also coming from a darker place, which makes artists in Minsk and Berlin somewhat similar.

Belarus has been the focus of political reporting for some time now. An autocrat, rigged elections, demonstrators locked up and tortured. When you talk to friends in Minsk, what do they tell you about the situation and the mood there? What impact does the situation have on artists there?

All conversations arrive at the same topic, exactly what you’ve just mentioned, but there’s also a need to reflect, to process this confusion and pain. It’s really heartbreaking to realise that this pain and danger is constant for people living there. They can’t run away from it, they can’t be distracted. It’s a permanent backdrop that takes a lot of energy, making people frustrated and unable to create. I’m glad that artists there still find some fire inside and turn it into new art and amazing projects, but it has become so much harder now.

Are you involved in the protest movement of the Belarusian diaspora? And what can be done to support the people in Belarus?

I attended some protests in Berlin in 2020, but then I found my own way to talk about things in Belarus that bothered me. These are personal artistic statements mostly through music or performances, where I feel most natural and honest. I really respect any kind of dialogue about the situation, which shouldn’t be forgotten. What we can do from here is just keep talking about it, never accept it as something normal, try to help those who need help and focus on love for each other. How to do it is an individual choice.

To end on a more positive note: It looks as if live concerts, cultural life and possibly even club culture will start again soon. What are your thoughts when you look back on the last one and a half years of the pandemic?

I look at it as evolution and movement. The pandemic is just the latest challenge for society to overcome, but there have been a lot, and there will be more. Every generation has to deal with some troubles. We’ve all learned a lot during this time, first of all how to engage in solidarity, forgiveness and patience. I feel really sorry, though, for those who have struggled. Most of my friends and music colleagues fared well, all things considered, and took this time as an opportunity to focus, to create something, to learn a lot of things and, finally, to relax and have enough time to watch the coolest movies at home without feeling FOMO. Now as everything is opening back up, I feel like people aren’t taking for granted all the little things and moments. The possibilities to meet, hang out and dance in a new way make everything so fresh and alive like never before.

Mustelide is playing on August 27th 18.00 at the Pavillon. Buy your tickets here!